Remember Me

Creative Team:

Director Gavin Webber,

Musical Direction, original composition Iain Grandage,

Choreography Gavin Webber and dancers Sarah-Jayne Howard , Grayson Millwood,

Performers: Hsin-Ju Chiu, Matthew Cornell, Kate Harman, Alice Hinde, Sarah-Jayne Howard, Kyle Page, Joshua Thompson,

Lighting Design Ben Cisterne, Bluebottle,

Sound Design Luke Smiles,

Costume Design Sarah Jobling;

Musicians (premiere Season)

Ian Brunskill – Percussion

Iain Grandage – Piano, Cello

Kirsty McCahon – Double Bass

Miki Tsunoda – Violin

Program Note

I don’t remember the first piece of music I wrote. I do, however, remember when I was about six years old sitting next to Gummy Worm (my mum) and asking her to notate my meanderings on the piano – I think they were entirely on the white keys. I had no desire at that stage to be a musician, let alone a composer.

But I do remember my parents’ endless investment of time in my music making, and the gradual transferral to me of their own deep love of music. I recall sitting around my grandmother’s piano in my teenage years, listening to Moonrise Waltz – a composition by my grandfather that was danced to in ballrooms of the 1920s. It affected me then – the power of memory – how my grandmother summoned her long-gone husband through the keys of a piano, and somehow brought a little of this man I never knew into my life. Moonrise Waltz was the starting point for this score, and is performed here in public for the first time since the 1920s.

In writing the remainder of the score for this piece, I am more aware than usual of my compositional influences – Sculthorpe, Edwards, Vine, Smalley, Mills, Knussen, Adams – and in remembering them, I thank all of them for their lessons, be they in person or on the page. I would also like to express my heartfelt thanks to Ian Brunskil, Kirsty McCahon and Miki Tsunoda who helped me perform this score during the premiere season in Townsville.

Review:

With the stage set as a cleanswept country hall, a live ‘band’ warming up, dancers milling with the folks in the front rows of the audience and a pleasant, expectant buzz, i was momentarily transported back to my childhood, attempting the pride of erin with my dad at the taradale hall and eagerly awaiting homemade butterfly cakes at supper. But dancenorth was just softening its audience up, genially inviting us in and entrusting us with the intimate minutiae of their own early lives to the 3/4 time of an airy waltz before exploding any expectations of a simple sentimental journey.

The Townsville based contemporary dance company’s latest offering, Remember Me, presented in collaboration with the Australian Festival of Chamber Music, further cements Dancenorth’s growing reputation for edgy and physical choreography, compelling narratives and willingness to incorporate a wide range of media into their performances. Composer Iain Grandage created the score for Remember Me after having worked with artistic director Gavin Webber on the dancenorth/Splintergroup production Lawn a couple of years ago, and was Webber’s first choice as composer for this project.

The concept for Remember Me was born from a chance encounter the company had when touring their earlier work, Underground, last year. Rehearsing at the historic World Theatre in Charters Towers, they followed the strains of music to find a group of sprightly 70-somethings enjoying an afternoon dance. Further enquiry revealed that this was a weekly ritual, a communal sharing of activity, afternoon tea and husbands: as Shirley explains during Remember Me, wives loan their men to the widowed ladies, “…at the dances, that is!”

Choreography and score for Remember Me were developed during several improvisational blocks involving the whole company. The trust between Webber and Grandage is evident in the final product: it is impossible to distinguish if the dancers are responding to the quartet of musicians or vice versa, and in some passages, the complicity is astonishing. Miki Tsunoda’s plaintive violin and percussonist Ian Brunskill’s flatlining wineglass accompany dancer Hsin-Ju Chiu’s memories of her brother. She apparently explains their games in Chinese as she puts a helmeted and somnambulent Matthew Cornell through a series of extraordinary manipulations which fall somewhere between a balancing act from a Chinese circus and pure sibling torture. Cornell’s core strength makes the complex moves appear completely involuntary, truly at Hsin-Ju’s mercy.

Josh Thompson and Kate Harman initiate another poetic sequence which begins with lagging mimicry of small gestures, becoming larger and larger, the lead and the mimic constantly swapping roles, to a soundscape of dreamy strings. They are gradually joined by Kyle Page and Alice Hinde, then Hsin-Ju and Cornell, and finally Sarah-Jayne Howard. Patterns formed by curtains, window frames and weatherboards fill the ‘walls’ (huge video screens) while the dancers move like falling dominoes in response to one another’s gestures, right down to the exhalation of breath, one after the other. Thompson and Hinde take it even further with a duo of dancer and shadow, one upright, one on the floor, seamlessly changing places and mirroring expressions, every gesture melding precisely to the music.

The screens periodically fill with footage of the Charters Towers’ social dancers telling us their lives. They appear chirpy, optimistic and grateful, though Webber’s intuitive editing poignantly hints at lost loves and lives (the long shot of an empty couch, for instance).

The audience gets to meet the social dancers in the flesh after the interval, as Gary the MC announces a jive and sets off another round of introductions, adding incidental details. The genteel dancehall ambience, the mingling of young and old dancers, lasts just long enough to warm and lull us before the social dancers retire, and the dance dissipates into a frantic sequence of panic and burnout culminating with an increasingly violent Harman kicking the inert Thompson across the floor, screaming at him to “get the fuck up.”

Breathing hard, Harman takes to the mike to deliver a soliloquy about love, loss and memory, asking us only to remember her if we can deal with what we see. The dancers line up each holding a framed picture of themselves as children as the screens fill with faded pictures of the social dancers in their prime.

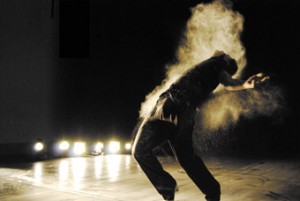

In semi darkness Hsin-Ju helps Thompson dress, like an elderly couple assisting one another. They lie down on the floor in an embrace and Page, the youngest, arrives to cover them with dust. Kirsty McCahon’s double bass and Grandage’s cello reverberate ominously as we witness this burial, this scattering of ashes. The dancers rise, breathing out puffs of dust, and their imprints

remain like an accident outline. The others return to daub one another, shaking off layers and

laying down more dust until they are all ghosts, floating and crumbling, falling and flailing, creating fog and patterns of increasing complexity on the floor.

The dancers spin on the floor, digging their own graves, as an old face and hand appear on the screen. Page and Harman repeat a haunting pattern of approach and retreat, macabre memories of love and desire, until Page is alone and all we hear is his failing breath and a bell tolling.

Bernadette Ashley, realtime 86